Photo Journal - India 2025

Click! The surge of the sound rekindles the inspiration of shooting. Over time, I had begun to miss the familiar feel of the metallic knob and the leather grip. I haven't been taking photos often anymore. Since I’d been living in Oakland for so long, I had a plan to step out a bit further so wonder could lead my way.

Even if your film roll is destroyed by an X-ray, it is a worthy endeavor. Do not lose faith in the practice, but also, do not shrug off an accident. Security check! AK-47s pointed at your bag of film in the Mumbai airport. These guys rarely appreciate the importance of personal film checks. I was often lucky as I proceeded on with my film intact. These were learning moments.

What is the importance of wildlife photography in a world where we have half a century of National Geographic magazines full of material? A lion or tiger from the 70s or 80s, shot with wondrous oranges and reds on Kodak stock, will inspire, but it will not show you the growth or desperation these animals face today. Demonstrate the current state of things with your photography, and it will serve its purpose. I do not focus on documentary filmmaking, but I care enormously about the health of our planet and its ecosystems. If I go out to photograph animals and the composition is formed around mounds of garbage, the image speaks for itself. Shoot what is there.

On my part, capturing these images appeals to the primal fear and fascination from being young. Somewhere in us is an acute understanding that the world survives on cannibalism. Feast your eyes on the violence and the strength of incredible biology. Inside the deepest darkest parts of our minds, it is blending and breeding this fear. And boy is that just fuel for the most inspiring elements in our stories; spoken, written, and painted. I want to have a deeper understanding of that, so it can grow enriched in my mind and my work.

My major goal in traveling to India was to locate and photograph an endangered species of crocodile known as the Gharial. These crocodiles are longer than most species; males growing up to 20ft long (females, 15ft) with long, thin, bulbous snouts perfectly evolved for catching fish. Their strange look always interested me and their location in deep India, made me curious. Why are these creatures more vulnerable than other species in its waterways? Throughout India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and areas of Pakistan live another species. Mal Mugger crocodiles, a smaller species of crocodile, are more aggressive and consequently hunted and killed in areas nearing human habitation.

Mal Mugger Crocodile, Roll 98 - ULTRA 400 - 120

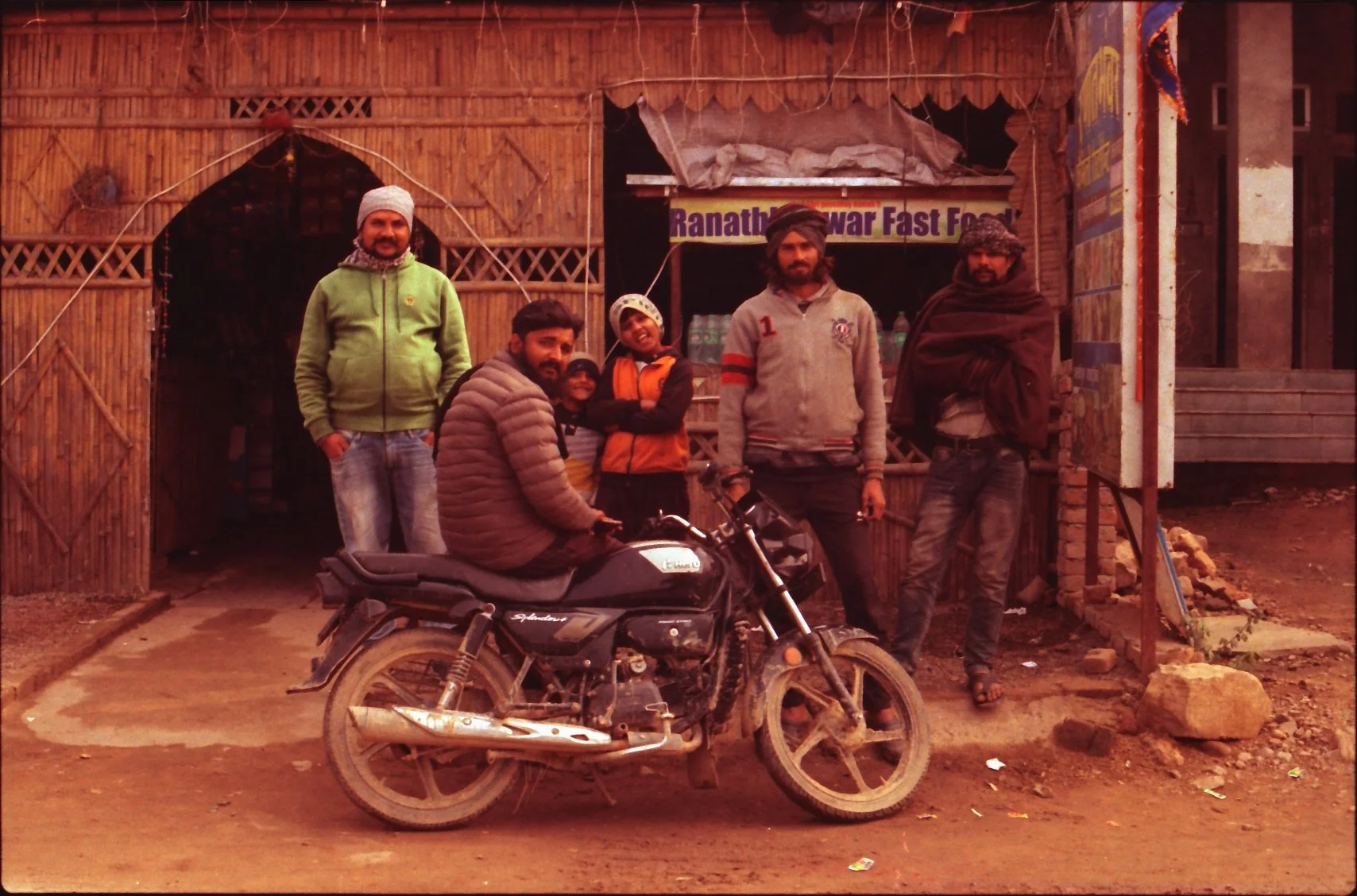

I began an expedition looking for waterways where these animals could be found, away from the cities. Not always so easy to get to. A long drive and boat ride. Some spots advertise this as a location for tourists. Navigate our purpose and reasoning and push on, locate our quarry. Nearly 400 kilometers south of Delhi is a city known as Ranthambore which is where I began. My first location marked on the map, day 5 in India. Outside of Ranthambore is a riverway where Gharial can be found in the National Chambal Sanctuary, protected from fishermen and hunters. It is regarded as having the highest population of Gharial in the world. These crocodiles are endangered and this section of riverway is protected under the government though you could not tell immediately.

The waterway was recognizably clearer than any other I had seen. The tours were not subtle. They traveled the riverway with gas-powered propeller motors, with several boats running at any time through the rivers. The disturbance was great.

The sun didn't break the morning fog. We moved under overcast skies in a great glow that clicked my lightmeter at an 11. I generally shoot at a higher shutter speed, never below 125. Most often, I squinted my eyes as we searched the shores for sunbathing crocs. Tall grass grew on the river sides where rocks stuck out of the waters. Several small crocodiles were found, but no Gharial. Part of me did not expect to see one. From a distance, after an hour, I noticed the first Gharial of my trip. I had my Mamiya ready with a 400mm lens, locked with Arista Ultra 400 Black & White Negative. I managed to take a few shots. A female, perhaps a 10-footer. We drew closer and the guide shut off the engine...we drifted closer and closer. Click. Click. And the animal shot off. Gone. The excitement was there but I was feeling like an imposter. I did not belong here bothering these animals on this boat. I knew I didn't want to be in a motorboat. I've seen how they can slice and gash a manatee in the Everglades. But these photos were why I had come. Keep it moving.

The Mal Mugger crocodile was much more common but I did not see another Gharial the remainder of time I spent in India. For 6 hours I repeatedly moved along the waterway, restricted by invisible borders the guides kept to. There were some sort of regulations I was not made aware of, with frustration, knowing that the crocodiles followed no borders and likely were basking in large groups just a bit further up the river. Bribery was met with open arms but when I asked to move forward beyond the apparent border, I was met with confusion and refusal.

The next day, I explored the Tiger Refuge in Ranthambore. This was another gas-powered tourist expedition. A line of jeeps waited with drivers hollering about. Monkeys hopping from the hoods onto trees. The experience was to enjoy the wonders of nature by jeep. With massive wheels moving along the ground of dirt and clay, we came to areas that were weathered into deep wells formed by repeated passage, from day to day, month to month, year to year. A bumpy ride and loud as hell.

We entered through gate 2 of 10. The lands were made up of gorgeous rock forms that shot high up with dry orange and brown rock. Trees and forests were dry this time of year but shallow creaks ran throughout. You could tell this region would be very different during the rainy season. It would be more of a marshland.

Ranthambore National Park, Roll 101 - Kodak TMY 400 - 120

Interesting to notice that some of the animals were familiar with all their visitors. Maybe they were patterned to the movement of humans in their zones. That is why no one is seeing tigers in the Tiger Refuge. Deer, langur (black footed and faced monkey), peacock, Kingfisher, and a few sleeping Mal Mugger, is what we came across. The photos I took were with a high shutter speed to compensate for the movement of the jeep, while keeping as closed of an aperture as possible for focus. The sun was making its way down slowly. It beamed brightly, descending down the sky. We squinted our vision as we peered through the tree cover. This ride was only 4 hours. I was treated quite well by the guides and drivers. I reminded myself that this was their job and these jeeps would move through these dirt roads 6 months out of the year.

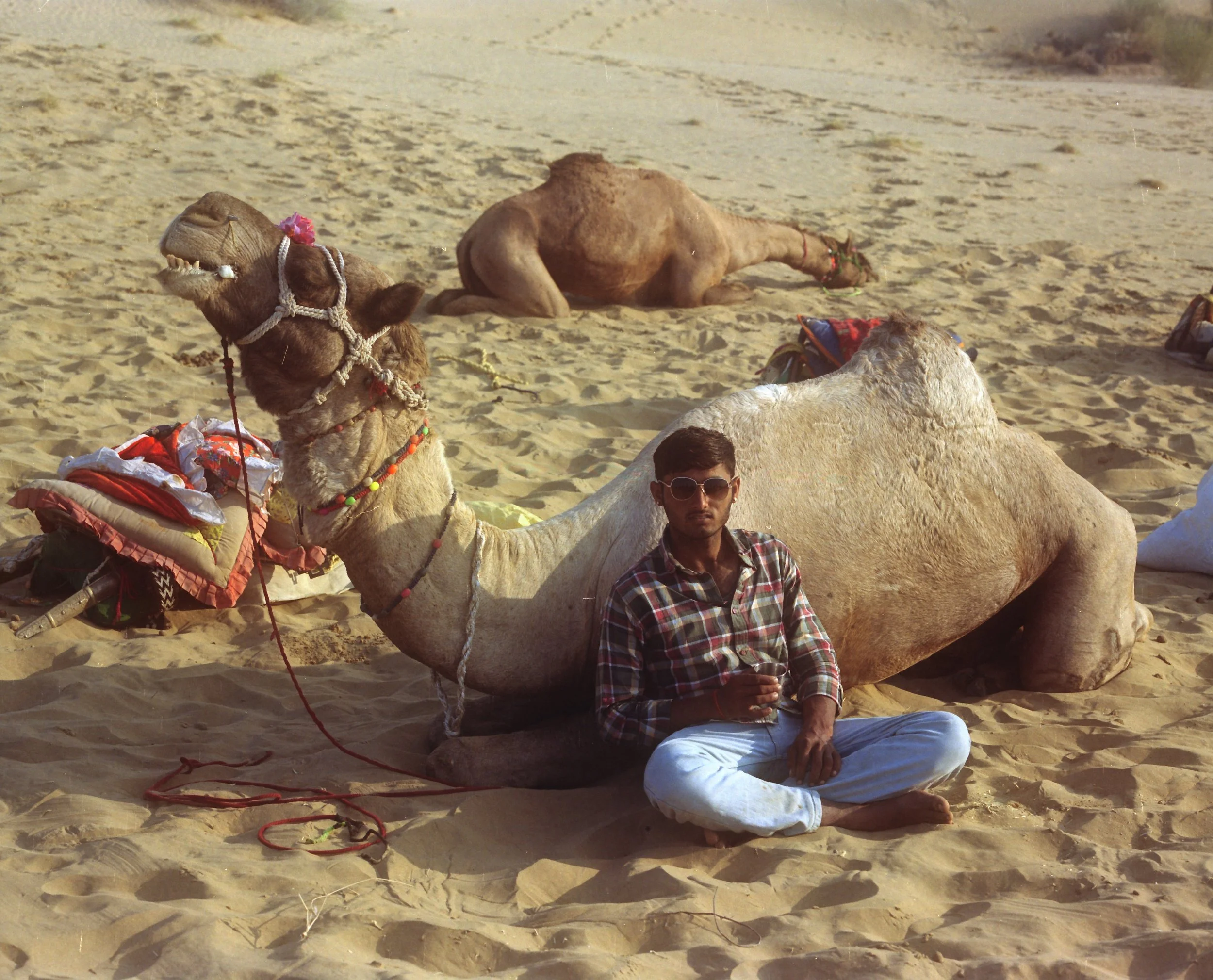

While grateful for the experience I was not pleased by the handling of the reserve with the jeeps. I also felt a sense of guilt and feeling a bit like an imposter as I rode along with so many other tourists and "safari goers". Curious if this was going to be the case everywhere, I continued traveling west into a region called Rajasthan. Jumping around different cities, I explored their markets and their many aged forts. It was common in these areas to see elephants mounted with large baskets for people to ride inside and camels strapped with large baskets of goods. For several weeks I moved through these cities, shooting, my negatives starting to stack up. I needed to return to New Delhi to drop off some rolls to be developed, and so I did. Having already spent several days in Delhi earlier in my trip I dropped my film off at the lab and continued on further eastward.

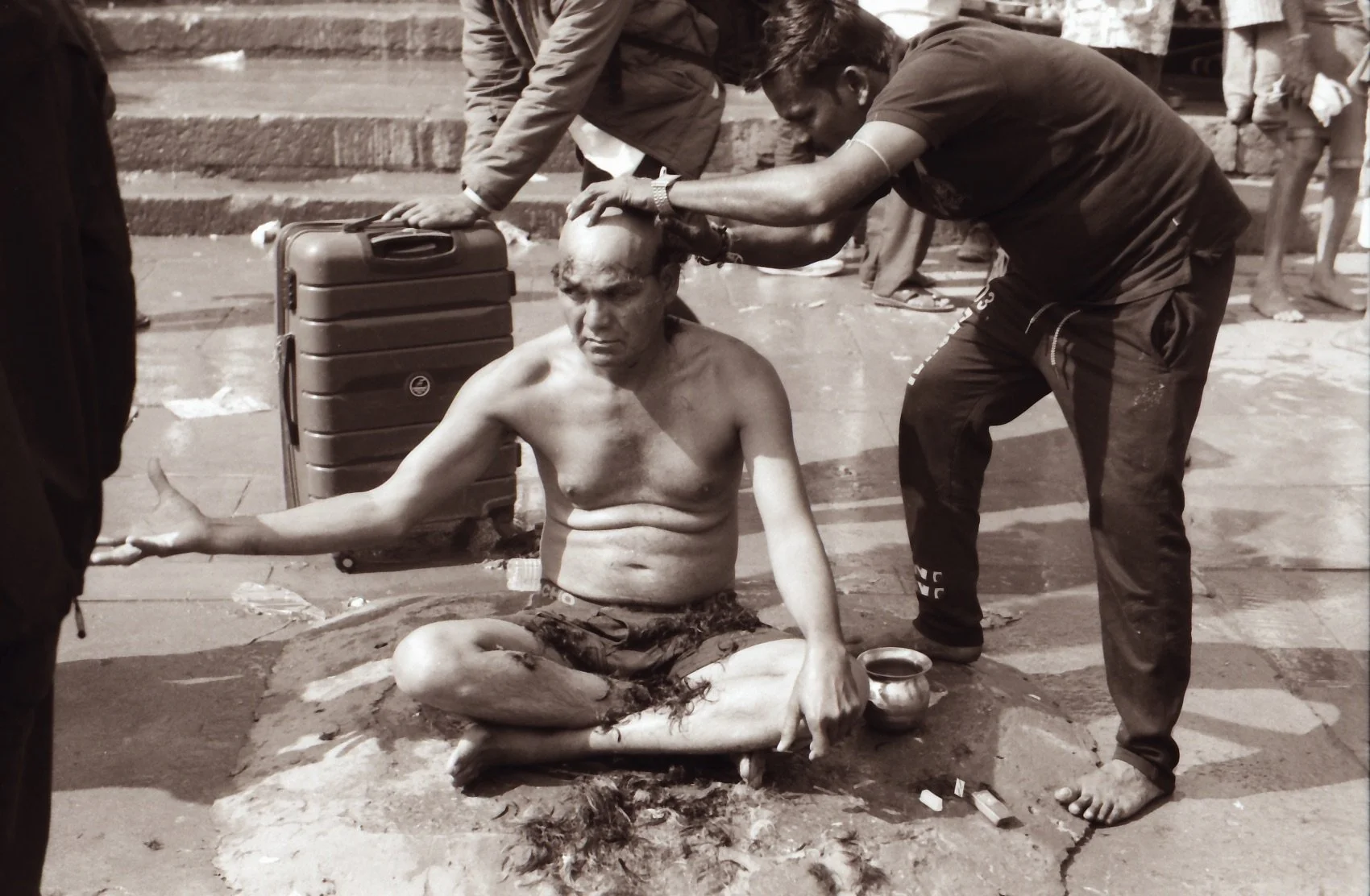

A day's train ride landed me in Prayagraj to experience the Kumbh Mela. Writing it that way makes it seem like a small thing, but it's anything but. I did not fully know what I was getting myself into. The Kumbh Mela is the world's largest religious gathering. It is a Hindu pilgrimage held every 12 years at the "Triveni Sangam" where the Ganges, Yamuna, and mythical Saraswati rivers meet. It is said that if you bathe in these waters at this time it is to grant you passage into heaven in the afterlife. I have never in my life seen so many people in one place in all my life. The comparison I keep making is like when you want to leave a music festival at the end and every exit is at a standstill. The sheer number is beyond that even. Try and comprehend this many people filling the streets and intersections for several city blocks. I have to admit this experience was insane, as well as my time within Varanasi, the most holy and ancient cities. It would be enough to fill many pages.

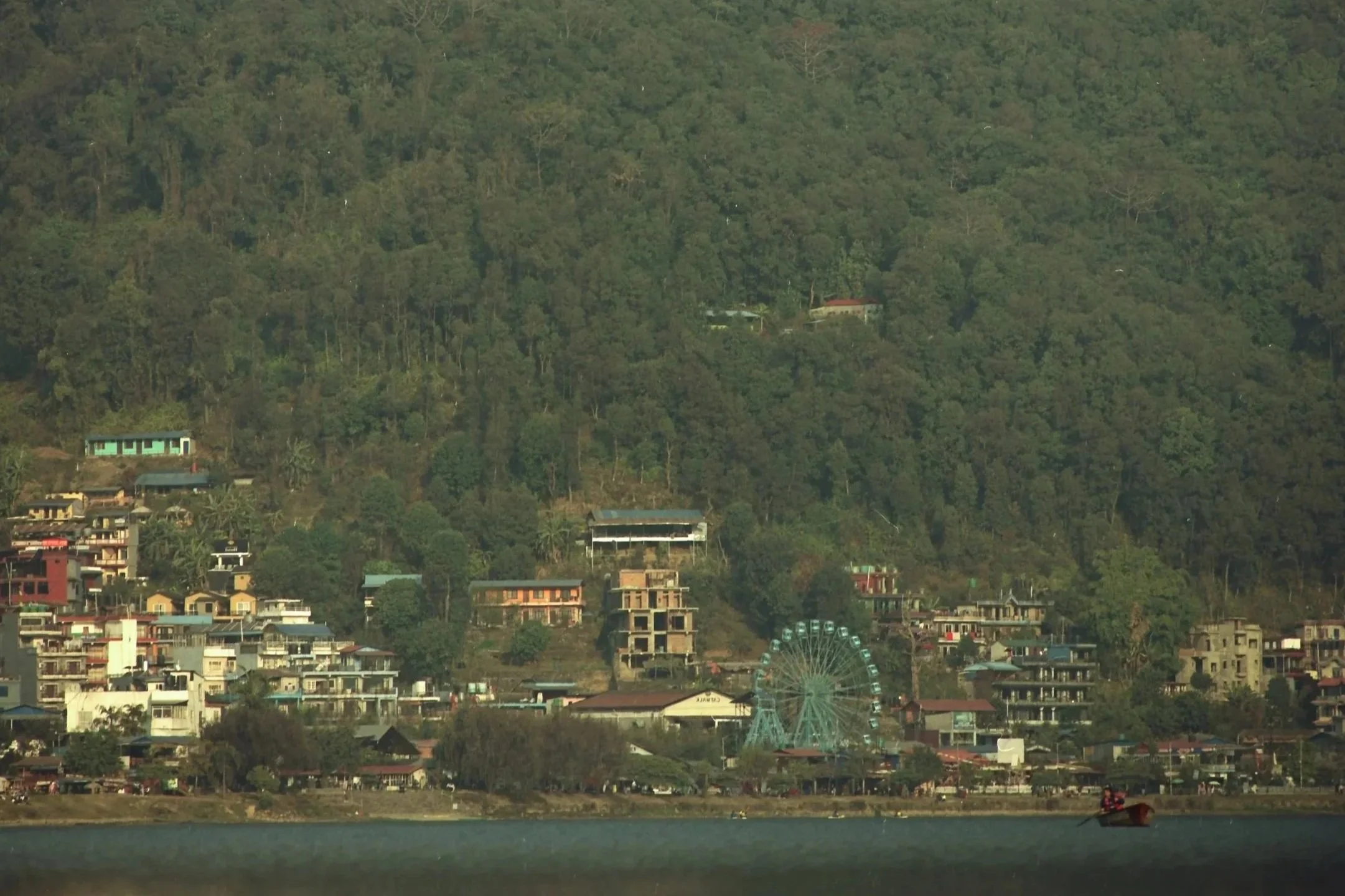

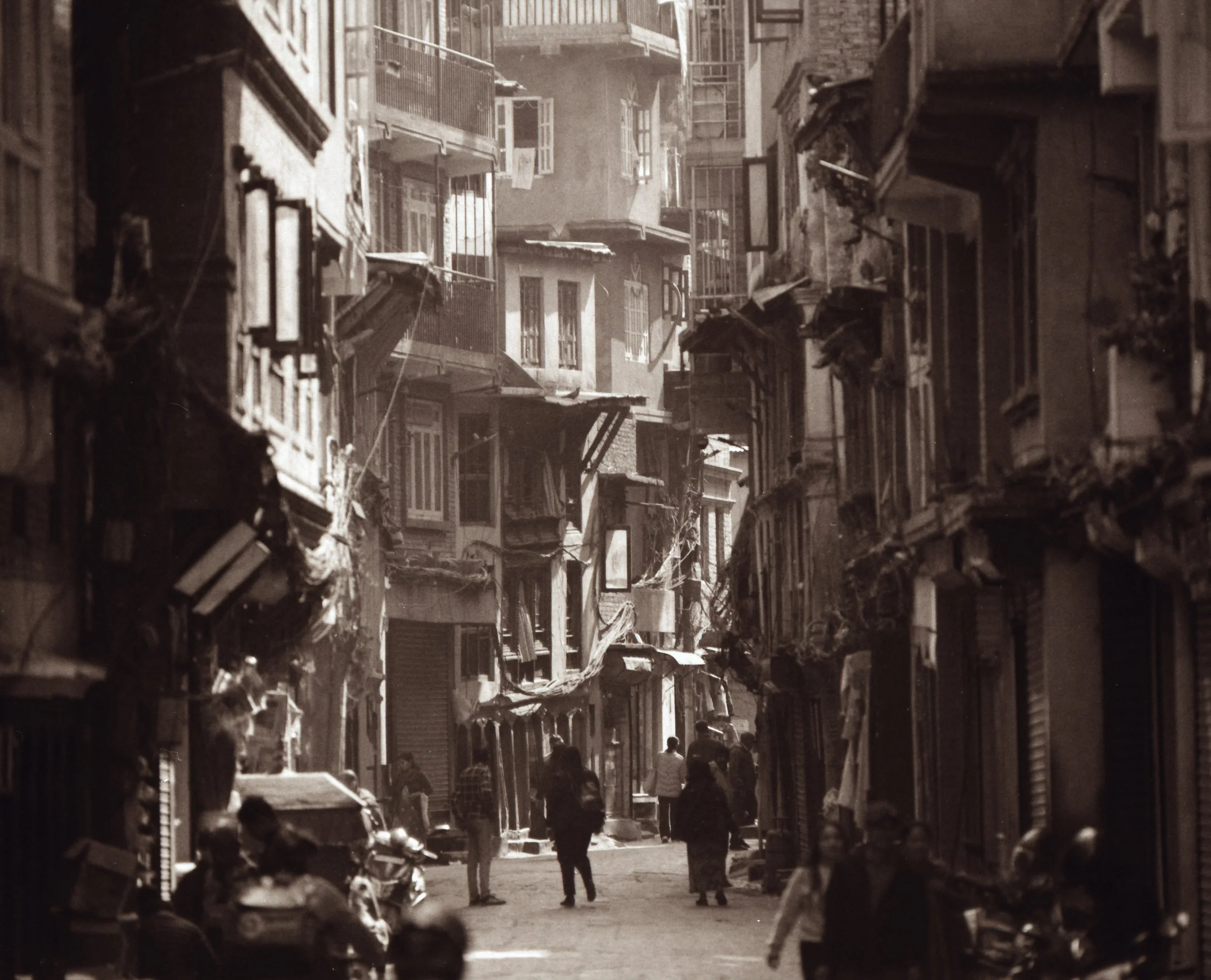

As an escape from the sprawling population of Varanasi I took a bus to India's northern border and entered Nepal. The quiet was absolutely therapeutic. It came over me like a soft breeze. A heavy weight was lifted from my shoulders as I explored the town of Pokhara by the Phewa lake. On a kayak I paddled out to glimpse the distant peaks of the southern Himalayas.

To get back to the large reptiles, I had to circle back down south a bit to where the land dips into warmer forested areas in the Chitwan National Reserve. Knowing that the previous river (Chambal) had the highest in population, I wasn't certain if I would see any Gharial.

The second I arrived in Chitwan I was met with a number of invitations to different hotels, hostels, and homes. The gentlemen were assertive. I had to take a moment to think how best to represent myself to get what I wanted. The issue with the Chambal river may not have been the population of crocodiles, but the willingness of the guides to explore deeper regions of the riverways. I was met by a confident man who seemed to be waiting for me, sitting upon his motor scooter with bad suspension. He showed me images of a homestay he would take me to and spoke of guides who would be happy to show me around. I did not want to waste time so I took him at his word.

The region is known for its wild rhino population that will not remain within the reserve. They are large animals and they go where they please. He said that they often move across the rivers through his community to get to the banana plants in his neighboring field. I would certainly see them, he promised. We took a long snaking road that fed into a tourist zone and out again, moving along the river. The bank was deep and sealed with large cemented egg-like rocks that would contain the river during monsoon season. I imagined how the ecosystem would change when that happened. The amount of water would drown so many trees. The ground that made up all I saw into the reserve would be the bottom of the river. You could see how the trees populated the higher ground and how dead trees crowded areas of deep rock. The water current would push the brush together like an enormous tumbleweed. Three small rhinos chewed on it.

Arriving at the man's "homestay" I discovered that it was not so much a homestay as it was the house that he built. Cement walls with a tin roof, a plumbing system and a lock for my door. My immediate draw was the story of the rhino and the river that ran right behind his home. He said crocodiles can sometimes be seen there. My thought is that if I can be near them even when I am not in the reserve, my chances of a better photo increase. I took him on it.

His wife provided dinner that day and he agreed to take me around the town to see what was available. I saw on the outskirts of the reserve a tiny tikibar. The river flowed along a forked path that flowed around the reserve like a border. I could see tiny deer moving about the shallows while several Muggar crocs and tiny Gharial sunbathed in the mounds of mud. We began the next morning.

Mist covered everything when I woke up. The sun rising gave everything a strange peach and orange hue. The flapping wings of water birds could be heard before they passed overhead and disappeared again through the mists. I was well ready when we hopped on the motorbike towards the river where large canoes lined up. Each had long poles to push us along like a Venetian gondola. It was myself, two guides, perhaps my age or even a bit younger, and the man who led the boat.

Within moments, I could feel a deeper connection with what I was there to do. There were no other tourists in other canoes. I could hear the trickle of the water as it ran along the rocks. The mist clung to the morning with a faint chill. The guides and I sat in silence. The guide clearly respected his position and had a love for the land and its creatures. A hornbill remains still at the end of an overturned tree resting in the water. His hand pointed outward towards it but he said nothing. Quietly, we passed a group of deer eating at the dense green tangle of vines and river grasses, faintly visible in the gloom.

My first roll was Kodak Gold 200. The light readings were low. With the moving of the canoe and the length of my lens, most of the images I suspected would be blurred until I could increase my shutter. I clicked off a few shots anyway. A lone man stands in his canoe with his long pole, a single grey green shape in the cloud. I waited a long time framing to decide what shape would read best. We drew closer and closer as I pulled my focus. My Kodak Gold was processed extremely dirty with many chemical artifacts but the mood did remain.

The sun was getting higher and the mists were fading away. I loaded in Kodak TMY 400, one of my favorite stocks. I was ready. There was nowhere else I wanted to be. I was doing it.

Just as the sun began to clear up the fog, we came to a bend in the river where the river beds mounded upward. It was right then I found what I was looking for. The mounds were lined with crocodiles sunbathing motionless. The man with his large stick slowed the canoe and strolled us in between a loop between the land and the large mound island. We slowed but did not stop and I raised my hand to slow him if I could. We stopped. The man held onto the pole but lowered himself to sit as I took in the view.

There must have been around 15 crocodiles on this little island alone. Several were Gharial and they lounged together with the other species. Some were quite large. Their weight swelled outward at the belly, moving inward and outward very slowly. I was not sure how long I would be able to sit there with them. Would the guides insist we continue on, I did not know, but I treated the moment as if it would be over at any moment.

Male Gharial in Chitwan National Park, Roll 109 - Kodak TMY 400 - 120

Shooting at a shutter of 250 I wanted to be sure the images were crystal clear with no motion blur at all. I wanted them to appear as almost sculptures of the creatures. As a black and white image we would be focused on the scales and the textures of them. Any blurring of them would ruin it for me. They were somewhat illuminated from behind also and I wanted to be sure the pictures were not blown out so I raised the aperture as well.

The guides were patient and when I signaled, they moved us along. A short way down the river it became more shallow and our pace slowed. Here we came across the largest Gharial of the trip. It was also one of the few, if possibly the only, male Gharial. It was around 15 feet long with a large bulbous snout, dwarfing the many females that lay around it. They seemed to be less skittish this time and only a few moved away into the water when we drew near.

At one point, we came to a large female Gharial resting submerged under the water. The very sight of it under the water, so close to us, gave me a strange unease that was absent until then. Did I not realize there were crocodiles submerged all over these waterways? The whole time they have been there, but seeing one had its effect. I stood up, keeping my balance, and attempted a shot with my wide lens. I shot 2 rolls of 120mm here before we reached a position where the guides brought us ashore to begin our hike through the reserve.

The experience was unbelievable. If I was bothered by the loudness of the jeeps before, this was the opposite to the far extreme. The Chitwan reserve is known for its high population of deer, python, rhino, elephant, tiger, leopard, and bears and we were making our way around on foot. I told myself to keep a weary eye and that I had two guides and these men were professionals. Their attentiveness was mine. I would be lying if I did not think that my being there in this way could have dire consequences, but I maintained that I came there for a purpose.

Passing through the reserve we saw each of the animals I listed, save for tigers, though I personally did not see the leopard. Its presence had spooked the herd of deer and they signaled aloud to each other across the forest that a predator was nearby. The forest would be silent and then we would hear the sound repeat for a time then we would hear the movement of them fall away through the forest. The remaining portion of the herd would continue to signal, a loud cry behind us and a soft one far off ahead.

We had another scare from a rhino later that evening. We came upon it, quite close. It was quietly chewing on some plants as we came around a corner into the open and I pointed it out to the guides. I did not think it was OK to be so close to the enormous animal, and when they saw it they felt the same. They moved us backward but the rhino was blocking our path back to our canoe, and the sun was getting (in my mind) dangerously low. If the predators are nocturnal hunters, we do not want to be wandering around trying to get back to the river in a pitch-black forest. We were delayed by the rhino and honestly I did not know what to think. The light was too low for photos so I had strapped it to my back. The guide tossed a stone at its side, but did not hit the animal. It moved away into the forest. We could hear and feel how big it was from its movements on the ground. It was very surreal. It moved far quicker than I would have imagined for something so big. All in all we must have waited around twenty minutes to get around the rhino and back on our path. We did not take any greater risk than described, but it stood out to me as one of the wildest experiences of this trip, if not my life.

That evening we made our way back across the river and into a compound at the top of the river bank. It was like a normal hotel with an outdoor common space in the center of many rooms. The only difference in this case was we could hear the loud busy howling of wild dogs or Dholes. They looked like stocky foxes to me as they chased one another up and down the muddy bank of the river. I saw one or two at first as my eyes adjusted to the light, but soon after I noticed many more. I ate my dinner and had a beer and went to rest for the next day's hike.

Renaldo the Elephant, Roll 111 - 120

Unfortunately for me I got hit by a bad stomach illness during the night that followed me through the jungle the next day. I maintained what self respect I could, but "when ya gotta go, ya gotta go." It was most apparent a problem when we were faced with a wild elephant that was staying the course of the reserves path system ahead of us. The elephant was referred to by the guides as Renaldo, and was regarded as a man-killer. I had heard the name Renaldo quite a bit by this time from others, so it seemed this elephant was as popular around here as the football player. Even if the elephant seemed to pay us close attention, it did not seem overly aggressive. It was unlikely to me that this was the infamous Renaldo. I took my chalky Loperamide tablets and held my stomach, took my shot, and continued on to the end.

On that day, we came across a crocodile rehabilitation center made specifically for the Gharial. Here, they attempt to protect hatchlings during the first month or two of their lives before letting them out into the river, this is in hopes of protecting them long enough to have a fighting chance. There were also adults, both male and female, who were held in protection. Several of these adults were suffering from severely damaged snouts. The worst of these was missing an entire lower jaw with only a stump of one, while its upper snout was broken in two down the middle. I suspect these were damaged from fights during mating season, where bones would not grow back. This would make hunting for them more or less impossible.

Why is this animal endangered, while the other species are not? The strange evolution of its long thin snout is perfect for catching fish, but not so good for aggressive altercations. The snouts appear to be delicate bones. There is no word that the Gharial fight with the more aggressive Mal Muggers, but it is probable as they share the same rivers. Over time, I imagine that these animal’s behaviors would grow to be more desperate and aggressive due to changing climates, population in decline for viable mates, and a decrease in possible food sources, which would all contribute to their depopulation.

Roll 109 - Kodak TMY 400 - 120

I would have liked to spend more time there in Chitwan. The photos I managed to get, I am very proud of. I was hoping to get one of many hatchlings gathered about an adult, but I missed the hatching time by a few weeks. After taking the time to do this and photograph these animals, I would return to this location for a longer and more focused time just on the river. And I would also want to revisit with the same two guides, for they were incredibly kind and knowledgeable, outstanding guys.

From here my trip shifted into one more as a vacationer I suppose. Joining with my girl friend we traveled around making our way south to find ourselves on our own sort of adventure. We did not go on another safari until we arrived in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka is different culturally than India and might I say, more accommodating for westerners. This also makes it far more expensive than India, and also more populated with Westerners. The vacationer culture seems to be something new that has taken root there and I think in part it is from Instagram influencers.

That being said, Sri Lanka has a vast, lush wilderness with all sorts of interesting creatures. I do not exaggerate when I say it displayed some of the most enchanting places I have ever encountered. With the jungle rocks and waterfalls high above sea level in the town of Ella, where its coveted trains pass through daily for travelers to witness the countryside. Personally, nothing can outdo the wondrous calm there was after a thunderous storm when the clouds of the night cleared away. We decided to walk, taking the path of the train tracks back into town. There was the distant sound of a waterfall you could not see in the dark until the moon came out. And as you walked along the wooden planks of the train tracks, looking up, you could see a great number of glowing insects that flew about the high branches of the trees like forest sprites. Typically, I was familiar with lightning bugs keeping mostly to the ground in the months of July and August on the East Coast of the USA, but these remained high up in the trees. And if you looked beyond the trees into the sky, it was nothing but stars because of how isolated our location was in the center of Sri Lanka. It was a cut out of a fantasy tale.

To conclude the journey, on the topic of safaris and the business of seeing animals in their natural habitats, I have gone on two other safaris. Both of these were within protected lands in Sri Lanka. The first being the jeep safari in Yala. The lands were beautiful, not far from the southern coast of the island. Literally where the jungle meets with the ocean, we could see crocodiles and elephants wandering about. Again, the lands were torn apart from the repetitive roaming of the jeeps but the animals seemed to be used to this. What was new this time was the absolute disregard for the animals personal space. If there was word of a tiger or a group of elephants, it would be radioed to the squad of jeeps and they would all zoom over. Imagine a small family of elephants moving over to take a quick shower in a watering hole and within moments, they are surrounded by jeeps on all sides. There must have been 8 jeeps, possibly more. These animals immediately hid the calf between the two of them as they continued to spray water on it. Considering what can be done to respect the land and its creatures, I can't help but think that people simply should just not be there. The irony is not lost on me. There is nothing more special about what I want than what many of these other travelers want. I am not a part of some grand group pushing for better treatment of these animals. What can I do but simply not participate? And yet, I have multiple experiences in these different reserves and I saw how these different locations handle the land. Without contest, Chitwan in Nepal was the best experience for me and I would guess for the animals as well. We did not make use of motor vehicles on land or water. That is not to say there were no jeeps; I did see jeeps with a few tourists in them, but I only saw one or two of them and these may have only been for dropping individuals off at the entry. The vehicles themselves are too large and cause too much disruption. These are gas-powered as well, which pour fumes into the air that the animals shouldn’t live around. Seeing a human should be foreign to them, but even more so, seeing a jeep should be unacceptable.

These animals are truly from a different era. When you stand near the massive size of a rhino or an elephant, you can't help but consider them as ancient. How can something so beautiful and unique survive in the modern world where there is such disregard? Big business is destroying everything, and even the business that requires these animals to function is doing them harm. If I have any right to go and explore these animals for the photos and inspiration, I feel it is also my responsibility to communicate this case. There are better ways to experience a safari, at least in many cases, than in enormously obnoxiously loud motor vehicles.

Douglas Lawlor, 2025